How the AC75 has grown up

I’ll never forget a moment in 2018 when Ben Ainslie stepped out of his office after a long call with Team New Zealand’s management. On that call, the AC75 had just been described to him – in words alone.

Ben grabbed a pen and did his best to sketch what he thought they were talking about. For the next few hours, sailors, designers and engineers crowded around that piece of paper, trying to make sense of a 75-foot foiling monohull that, at the time, felt more science fiction than sailing boat. For me, that was the day the AC75 was born.

Fast-forward to today and we’re entering the third iteration of the AC75 – and that matters. For a decade, the America’s Cup lurched from one radical class to another. While that drove rapid innovation, it also produced huge performance gaps and, at times, racing that was decided long before the start gun.

Every sailor has their favourite Cup boat. I still believe the International America’s Cup Class (1992-2007) was the finest I’ve raced, even if older generations will swear the 12 Metres defined the golden era, and younger sailors will laugh at the idea that a boat doing ten knots in all directions could ever rival an AC75 for excitement.

But across every generation, there’s one point of agreement: when a class rule sticks and evolves into its second, third and fourth generation, the racing gets better. Designs converge, sailors sharpen their edge and the margins shrink. That’s exactly what we’re heading towards in Naples — and if history is any guide, the racing in 2027 will be even closer than what we saw in Barcelona just 15 months ago.

One of the easiest traps to fall into when talking about the America’s Cup is obsessing over the rules (never my strong point!). Box sizes, foil limits, control systems – they matter, of course – but they’re not where the real story lives. The real story is on board the boat. And from a sailor’s perspective, the AC75 has changed more in feel than it has on paper.

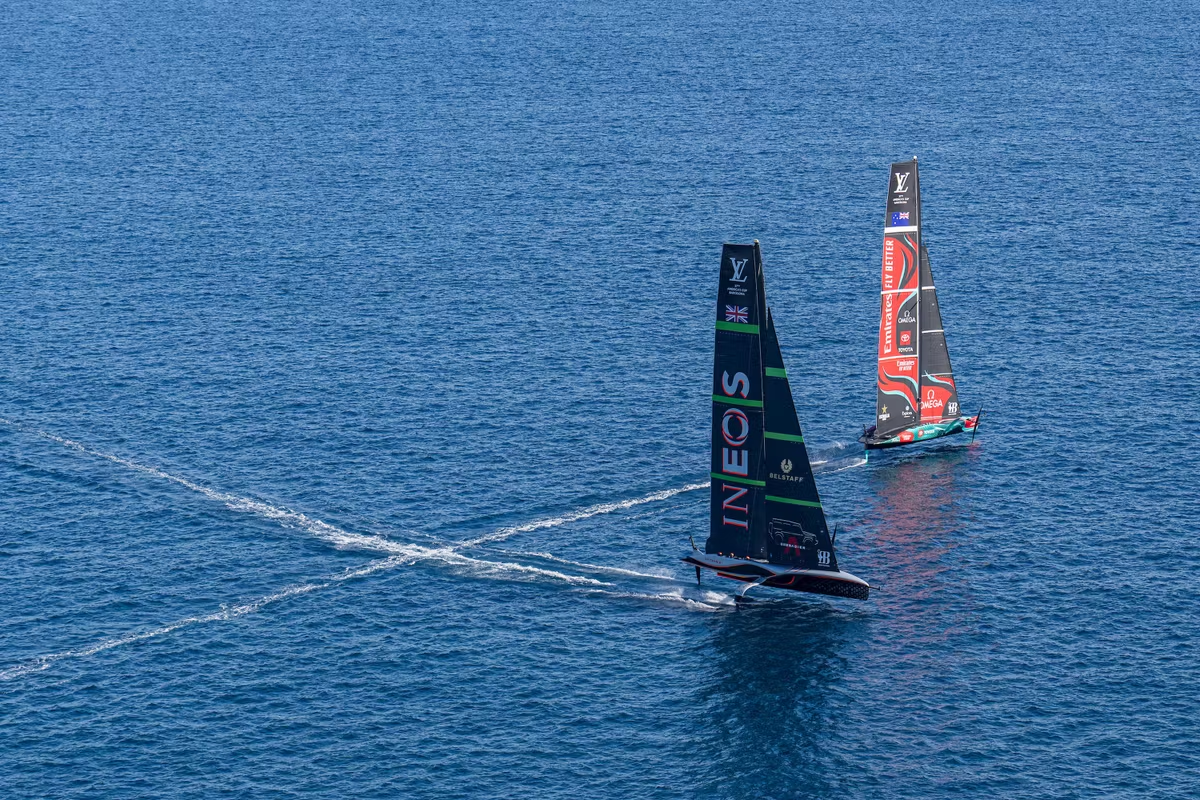

If you step back and look at the last three cycles – Auckland, Barcelona and now Naples – what you’re really seeing is the AC75 growing up.

Auckland: learning how not to fall off the knife edge

At AC36, we were still learning how to survive these boats. We spent hours on end just trying to control RB1, the first stab at an AC75. She was a cruel mistress: raw, unpredictable and often uncomfortable to sail. Foiling wasn’t a given – especially at the lower end — and once you were up, staying there took constant attention. You were always one small mistake away from a big one.

RB2, our race boat for AC36, was a nice progression, but it felt like the boat was always asking questions. Ride height would wander, modes were narrow and the feedback loop between the boat and the sailors wasn’t always clear. You’d make an input, wait a beat and hope the response was what you expected.

When asked the most nervous I’ve ever been on a boat, my mind instantly drifts back to my grinding trench on the starboard side of RB2. Wrestling her downwind in a big breeze was a battle I felt privileged to experience – but one I have no desire to relive.

A lot of performance came from simply keeping the thing under control. If you could get around the track without a major wobble, you were already doing a decent job. Racing was often decided by who made the fewest errors rather than who sailed the fastest lap.

It was exciting, but it was also exhausting. You were reacting all the time.

Barcelona: performance was there – if you dared to use it

By the time we got to AC37, the boats were better understood. That didn’t make them easier – in some ways it made them harder.

Britannia was, without a doubt, the most extraordinary boat I have ever sailed. When she was locked in, she felt almost otherworldly. Sailing downwind at 50 knots became an everyday occurrence – a ridiculous norm in this remarkable vessel.

The big gains in Barcelona were in the details. Everyone could foil very consistently. Everyone could get around the course super clean. The difference was how close you were prepared to sail to the edge.

The boats felt more stable, but the margins were finer. You could push harder in manoeuvres, run higher ride heights, trim more aggressively – but only if everyone on board was perfectly aligned. One mistimed input, one slightly late call, and you paid for it immediately.

The manoeuvres became the battleground. Tacks and gybes weren’t just about getting through cleanly; they were about how much speed you could carry, how quickly you could re-establish mode and how confidently you could commit.

From my cyclor cockpit, it felt like the boat concept had more to give – but only if you trusted it, and trusted each other. The sailor’s job shifted from “don’t break it” to “extract everything without tripping over the limits”.

Naples: consistency beats brilliance

Now, looking ahead to AC38 and V3 of these boats the most noticeable change won’t be raw speed – it’ll be consistency.

The boats will be more predictable. The systems will be cleaner. The behaviours better understood. And crucially, the performance window is wider. That doesn’t mean the boats are slower or duller; it means the fastest mode is easier to stay in.

The priority now isn’t chasing peak numbers – it’s minimising losses. A boat that’s half a knot faster for ten seconds but falls out of mode twice a lap will lose to the boat that just keeps rolling.

It will be a game of chasing ultimate control. My suspicion is that hardware across the teams – aside from the recycled hulls – will look broadly similar. The teams that control this hardware most intelligently may gain a decisive advantage over the others.

What we can all recognise is that the defenders already hold a substantial edge in their mastery of the AC75. Their software programme that controlled the boat was a step beyond the other teams previously. Is there enough time to close this gap?

Manoeuvres will be committed to earlier. Calls will be made with more confidence. The feedback from the boat will support decision-making rather than surprising you mid-turn.

This will change everything for sailors, less drama, fewer heroic saves and more quiet efficiency. That’s not boring – it’s high-level sailing.

I really hope that with V3, as the design freedom has narrowed and boat performance converges, sailing skill will come back to the fore. Communication will matter more than ever, as the racing will be decided on tactical calls and match racing brilliance. That is what we want from the America’s Cup.

The AC75 started life as an experimental concept – spectacular and slightly terrifying. It’s now a refined racing machine. The rules have done what good rules should do: closed off the outliers and forced convergence.

What’s left is sailing.

That’s the most exciting part of where the Cup is heading.

Articles You Might Be Interested in

The results are in! What's missing in sailing media?

From coach boat to control room: How data and AI are redefining coaching

The Foil Weekly Wrap - 2 Feb '26

Iain ‘Goobs’ Jensen joins ETNZ

How SailGP decides who's right at 50 knots

Where America’s Cup careers will be made

The Foil Weekly Wrap - 26 Jan '26

AC38: 6 key questions that still need answers